Energy projects and social licence

04 December 2025

In February 2019, the Land and Environment Court of NSW (LEC) handed down its decision in Gloucester Resources Limited v Minister for Planning [2019] NSWLEC 7 (Rocky Hill). Rocky Hill involved an appeal against the (then) Planning and Assessment Commission’s (PAC) refusal of the Rocky Hill Coal Project. The Rocky Hill decision was seen (and reported at the time) as ground-breaking – one of the first decisions of the LEC to emphasise the importance of climate change in the assessment of development applications under the NSW Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (EPA Act).

In November 2020, following the Rocky Hill decision, the NSW Government released the NSW Electricity Infrastructure Roadmap (Roadmap). The Roadmap was promoted as being the State’s 20-year plan to transform its electricity system and transition the electricity network to replace retiring coal-fired power stations.[1] In November 2024, the NSW Government announced the new Renewable Energy Planning Framework to support the Roadmap and 'deliver a clean, affordable and reliable energy system'.[2]

Most recently, the Planning System Reforms Bill 2025 (passed by both houses on 11 November 2025) proposes an amendment to the objects of the EPA Act to include the promotion of 'resilience to climate change and natural disasters through adaptation, mitigation, preparedness and prevention'. Further information in this article - New NSW Planning Reforms - Part 2 - Administration and Planning Authorities.

In this article, we explore the noticeable shift in the treatment of more 'traditional' resource and energy projects (i.e., coal mines and coal-fired power stations) by the NSW Government and the LEC and whether renewable energy projects enjoy the benefits of a 'social licence' in the post-Rocky Hill era, that other energy related projects struggle to achieve.

A brief history of coal mining in NSW

Coal production’s long history in NSW was touched on in the first article of our Navigating Renewable Energy series. Coal was first discovered near Newcastle in 1796 and has significantly contributed to the NSW and Australian economy since that time. Until about 1985, NSW remained the largest coal producing State producing nearly 88,100,000 tonnes at that time.[3] The mining booms in the late 1970s/early 1980s and in the early 2000s (up to about 2015) saw exponential growth in the industry – both in terms of prices for commodities like iron ore and coal as well as new (and expanded) coal mine developments. Coal export volumes from NSW to the rest of the world have doubled since 2001, from 75 million tones to over 164 million tonnes in 2018.

The Parliament of New South Wales Coal mining in NSW: key statistics research paper provides the following summary of the coal mining industry as at September 2025:[4]

- In 2023-24, the coal mining industry produced 173.5 Mt of saleable coal

- In 2023-24, coal was NSW’s largest export.

- NSW currently has 35 operational coal mines located across the 5 major NSW coalfields (Gunnedah, Hunter, Newcastle, Southern and Western) and the Gloucester Basin. As of September 2025, mine owners are seeking planning approval for extension of 12 operational mines and 3 mines that have been placed in care and maintenance. Increased coal extraction within the same approval period is being sought for 2 coal mines.

The NSW Government’s Strategic Statement on Coal Exploration and Mining in NSW (2020) (Strategic Statement) confirms that, over the long term, the future of the NSW coal industry will be “directly affected by the global transition to lower carbon sources of energy”. The NSW Government is currently reviewing the Strategic Statement. The review is likely to reflect the Government’s other policy settings around the transition to renewable energy.

Transition to renewable energy in NSW

Beyond Sydney and the Hunter, towards any regional centre in NSW, the growth of renewable energy projects is evidenced by the visible rows of solar panels and wind turbines. In the first half of 2025, electricity generated from renewable sources also surpassed the amount of energy generated from coal for the first time globally and in Australia.[5]

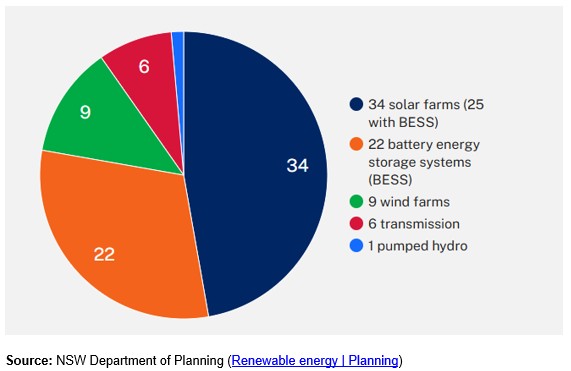

The NSW Major Projects portal shows that there has been an increase in the approval of renewable energy projects over the past 5 years. Since November 2019, the NSW Department of Planning has approved (as at August 2025):[6]

- 72 projects that support the renewable energy transition

- 12.73 GW of new generation projects

- 14.3 GW of energy storage system projects

- 2 GW of long duration storage projects

On the other hand, while there have been modifications to existing developments consents, no new coal mining development consents have been granted since 2022 (noting the recent decision in the NSW Court of Appeal[7] to overturn the decision of the Independent Planning Commission (IPC) to approve the Mount Pleasant Optimisation Project to extend the existing development consent for the Mount Pleasant Coal Mine in the Hunter Valley for a period of 22 years).

Social licence

Coal mining projects are currently controversial. Community views are a mandatory consideration for consent authorities when assessing development applications under the EPA Act. This assessment process usually involves weighing the impacts of the proposed development (including environmental impacts on both the natural and built environment as well as social impacts) against the benefits of the proposal (usually economic and social). More recently, in the face of increasing public and political concern about climate change, that balancing exercise has resulted in the refusal of coal mining related applications.

The Rocky Hill decision, for example, received significant media attention because of the assessment undertaken of climate change impacts. This was not, however, the only reason the project was refused. The Rocky Hill Project (Project) was the subject of significant community opposition. During the public notification period for the amended development application, the PAC received over 2300 objections to the proposal raising concerns about the potential noise and dust impacts of the mine, the adverse impacts on the visual amenity and rural and scenic character of the Gloucester valley, and the social impacts on the Gloucester community (as well as concerns that the opening of a new mine would contribute to climate change). A local community action group, Groundswell Gloucester Inc, were ultimately joined as a party to the LEC proceedings. Chief Justice Preston determined that the negative impacts of the Project outweighed the economic and other public benefits of the Project. The Court found '… the Project will have significant and unacceptable planning, visual and social impacts, which cannot be satisfactorily mitigated. The Project should be refused for these reasons alone.'[8] The greenhouse gas emissions and their impacts were stated to '… add a further reason for refusal.'[9] His Honour found:[10]

The mine will have significant adverse impacts on the visual amenity and rural and scenic character of the valley, significant adverse social impacts on the community and particular demographic groups in the area, and significant impacts on the existing, approved and likely preferred uses of land in the vicinity of the mine. The construction and operation of the mine, and the transportation and combustion of the coal from the mine, will result in the emission of greenhouse gases, which will contribute to climate change. These are direct and indirect impacts of the mine. The costs of this open cut coal mine, exploiting the coal resource at this location in a scenic valley close to town, exceed the benefits of the mine, which are primarily economic and social. Development consent should be refused.

The Rocky Hill decision continues to inform decisions about coal mines and the need to consider impacts of greenhouse gas emissions from the burning of coal (scope 3 emissions). In Denman Aberdeen Muswellbrook Scone Healthy Environment Group Inc v MACH Energy Australia Pty Ltd[11] the NSW Court of Appeal set aside a decision of the LEC, confirming that a planning authority must take into account the likely impact of proposed development “in the locality”. This included, when determining an application for a coal mine, the effects of global warming contributed to by the burning of coal. Her Honour, President Ward held at [106]:

The Commission was required to take into account the “likely impacts of the Project, including environmental impacts on both the natural and built environments, and social and economic impacts in the locality”. This required the Commission to consider the causal connection between the Project and its impacts on the environment in the locality of the Project. In Gloucester [Rocky Hill], the fact that the Project would only minimally contribute to global GHG emissions did not affect the need to consider the effects of those emissions in the locality (see Preston CJ at LEC at [514]-[515]).

While renewable energy is considered a 'cleaner' form of energy production (in particular, in terms of greenhouse gas emissions), renewable energy projects still face opposition.

Approvals granted by the IPC for the Valley of the Winds Wind Farm (about 94km north-east of Dubbo), the Wallaroo Solar Farm (near the NSW/ACT border in the Yass Valley local government area) and the Hills of Gold Wind Farm (about 60km south-east of Tamworth) are currently the subject of objector appeals in the LEC.

A proposed offshore wind project in the Port Stephens local government area was abandoned earlier this year following significant community objection to the proposal.[12]

Notwithstanding this, nearly all SSD applications for solar and wind farms lodged since 2019 have been approved (either by the Department of Planning/IPC or the LEC).

By way of example, each of the above renewable projects were objected to by the public during the notification of the development applications (94 objections were lodged against the Valley of the Winds Wind Farm, the Wallaroo Solar Farm received 97 objections and 280 objections were submitted for the Hills of Gold Wind Farm). The Department of Planning and IPC were, however, satisfied that the projects were in the public interest and the potential impacts on the environment and community raised in the public submissions could be managed by conditions of consent and were outweighed by the benefits to the local community (including employment and monetary contributions) and the NSW economy.

It appears that, for now and the foreseeable future, Government policy, including the NSW Government Net Zero Plan, is setting the scene for a fast-tracked and Government supported transition to renewable energy. That policy position is partly based on an implied social licence for renewable energy projects that is not enjoyed by other energy related projects.

Queensland’s Energy Road Map

The Queensland equivalent of Rocky Hill was the decision of the Land Court in Waratah Coal Pty Ltd v Youth Verdict Ltd & Ors (No 6) [2022] QLC 21. The Land Court considered the impact of a mining lease for a coal mine in Queensland’s Galilee Basin on human rights as a result of greenhouse gas emissions and their contribution to climate change. Although the application was ultimately refused, subsequent decisions of the Land Court have not necessarily led to the same determinative consideration of climate change.[13]

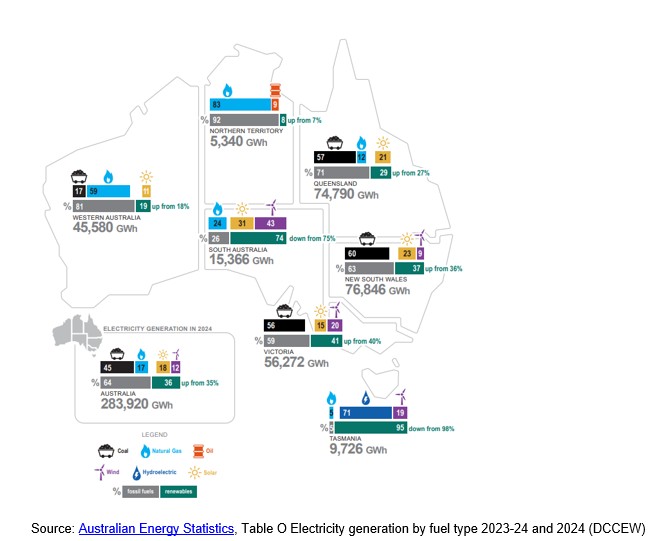

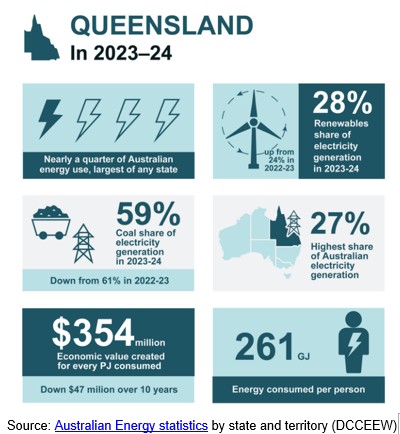

In Queensland there was 8 GW capacity in coal-fired generation in 2025, making up 60% of total power generation.[14] The balance was comprised of gas, storage, wind, large-scale solar and rooftop solar.[15] The energy landscape in Queensland is not dissimilar to NSW. Data published by the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) demonstrates that NSW is only marginally ahead of Qld in terms of renewable energy generation.

Both States consume the largest share of the country’s energy. Queensland also contributes the highest share of electricity generation.[16]

Acknowledging its role as a significant consumer and generator of electricity for the country, the QLD Government released its Energy Road Map (Energy Roadmap) in October 2025. The Energy Roadmap outlines the framework for the delivery of affordable, reliable and sustainable energy in the State through a focus on investment, infrastructure, community consultation and decision-making.

The Energy Roadmap Amendment Bill 2025 supports the framework by proposing amendments to existing legislation to facilitate the objectives of the Energy Roadmap. This includes changes to simplify the administration of the legislation, introducing flexibility and efficiencies to planning frameworks, and clarification around public ownership provisions.

A key component of the Energy Roadmap is the retention of state-owned coal assets for their technical life on the basis that this will significantly reduce overall household costs compared with an accelerated closure strategy.

One of the challenges addressed in the Energy Roadmap is community opposition to renewal energy projects.

The Rockhampton region has been met with a number of renewable energy proposals including a battery storage facility which has been the subject of a recent Planning and Environment Court appeal.[17] The appeal was commenced against Rockhampton Regional Council’s refusal of a development application and was ultimately successful.

The Council has expressed the importance of renewable energy projects being subject to a planned and coordinated State government led assessment.[18] In the interim, the Council has proposed a Temporary Local Planning Instrument for Renewable Energy and Battery Storage in an attempt to strengthen the local planning scheme by setting additional assessment benchmarks for the assessment of renewable energy projects.[19] The public consultation undertaken for the draft instrument revealed the community’s concerns surrounding rural amenity and a loss of agricultural land, development setbacks, amenity and health impacts, waste management and decommissioning and property value.[20]

In response to community concerns of this type, the Energy Roadmap recognises the need for a coordinated approach to development assessment and puts forward the development of a code to guide the conduct of renewable energy developers.[21] The Energy Roadmap commits to ensuring public engagement and public benefit are core components of the State’s renewable energy vision.

In the context of those principles, the Energy Roadmap refers to the Planning (Social Impact and Community Benefit) and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2025 which took effect in June 2025.[22] The Act introduces a community benefit system (comprised of a social impact assessment and community benefit agreement) to precede development applications for large-scale solar farms and wind farms. These projects are subject to public consultation and are assessed by the State under recent changes made to the planning framework.

The State Government has also introduced a Social Licence in Renewable Energy Toolkit[23] to assist local governments in navigating development for renewable energy. The announcement came with a funding commitment to update course requirements that will upskill future town planners who will play a critical role in the sector.

Like NSW, Qld’s Energy Roadmap promises a government led transition to renewable energy that addresses the current challenges being faced by the renewable energy developers. The Energy Roadmap also targets the communities whose support will be required to ensure its can be achieved and that renewable energy projects have the social licence to operate.

[3] NSW Parliamentary Library Research Service, Coal Productions in New South Wales, John Wilkinson (Briefing Paper No. 10/95)

[4] Parliament of New South Wales Parliamentary Research Service, Coal mining in NSW: key statistics, Daniel Montoya, September 2025

[5] Global Electricity Mid-Year Insights 2025 | Ember; Electricity from renewables overtakes coal in Australia for the first time | Energy | The Guardian

[7] Denman Aberdeen Muswellbrook Scone Healthy Environment Group Inc v MACH Energy Australia Pty Ltd [2025] NSWCA 163

[8] Gloucester Resources Limited v Minister for Planning [2019] NSWLEC 7 at [556]

[9] Gloucester Resources Limited v Minister for Planning [2019] NSWLEC 7 at [556]

[10] Gloucester Resources Limited v Minister for Planning [2019] NSWLEC 7 at [8]

[11] [2025] NSWCA 163

[12] Equinor scraps Hunter offshore wind project amid global woes | Newcastle Herald | Newcastle, NSW

[13] BHP Coal Pty Ltd & Ors v Chief Executive, Department of Environment, Science and Innovation [2024] QLC 7.

[14] Coal - QLD Treasury.

[15] Page 13, Roadmap.

[16] Australian Energy Statistics (DCCEW).

[17] Energy Storage Project No 12 Pty Ltd v Rockhampton Regional Council & Ors – Planning and Environment Court Appeal No. 148/2025.

[18] In response to the Planning (Social Impact and Community Benefit) and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2025.

[19] VIEW DRAFT TEMPORARY LOCAL PLANNING INSTRUMENT | Temporary Local Planning Instrument (TLPI) - Renewable Energy and Battery Storage | Engage Rockhampton Region.

[21] Page 11.

[22] Page 52.