From breach to brief: preserving LPP in a rapidly unfolding cyber breach

09 June 2025

A recent Federal Court judgment regarding the 2022 Medibank data breach highlights the importance of preserving legal professional privilege in expert reports prepared following a data breach.

In that case, Medibank was unsuccessful in its attempt to claim legal professional privilege over three reports prepared by Deloitte in response to the very public data breach.

While the law surrounding legal professional privilege is well established, the unique nature of a data breach is different, as was observed by Justice Rofe, in the Medibank Decision, ‘the production of the documents must be viewed in the context of the rapidly unfolding Cyber Incident… .’[1]

The Medibank breach

In late 2022, Medibank experienced a cyber-attack during which threat actors accessed its IT systems using stolen credentials and exfiltrated approximately 520GB of data, affecting 9.2 million customers.

After failing to extract a ransom payment from Medibank, the threat actors began releasing the sensitive customer data on the dark web.

As part of Medibank’s response to the cyber security incident, it engaged with external cyber security consultants to investigate and assist with a response plan. Medibank claimed legal professional privilege over all its reports and communications.

The ‘dominant purpose’ test

The test for professional legal professional privilege is an objective test of whether the confidential communications in question were made for the dominant purpose of obtaining legal advice or for use in contemplation of litigation.[2]

In the Medibank Decision the Court observed that it is ‘not sufficient that giving or obtaining legal advice or providing legal services was in part the purpose; it must be the dominant purpose of the relevant communication.’[3]

Furthermore, the purpose must be assessed at the time the communications occurred.

What was said and done

Medibank engaged its lawyers and cybersecurity experts to prepare several reports, all labelled as being prepared for the dominant purpose of obtaining legal advice.

This occurred during a busy period as events unfolded rapidly with different issues arising in quick succession including the breach, the basis of the attack, the data taken, the subsequent ransom demand and whether to pay it. In addition, numerous stakeholders and decision-makers were being called upon or were asking for updates.

In the glare of public and regulatory scrutiny, Medibank made several statements and took steps to establish other purposes, which the Court used to determine the purpose for each document. The Court categorised these purposes as follows:

Third parties and agents

Businesses are increasingly engaging with external cybersecurity and technology experts to help them contain and understand the circumstances of a cyber incident and respond to regulatory investigations or mandatory reporting requirements.

However, it is important that these third-party agents are engaged for the dominant purpose of gaining legal advice or in anticipation of litigation. Simply stating this purpose is insufficient to establish legal professional privilege and 'is not established by bare ipse dixit'.[4] (that is: just by saying it doesn’t make it true).

It is also important to consider that legal professional privilege is also not established ‘to third party advices to the principal simply because they are then ‘routed’ to the legal adviser.’[5] Merely labelling reports or communications as confidential and protected by privilege is insufficient to satisfy the dominant purpose test.

What documents were privileged?

Justice Rofe determined on the evidence provided by Medibank that, despite the rapidly unfolding circumstances, some communications and reports did satisfy the dominant purpose test for obtaining legal advice and preparing for litigation. These included four reports produced by CrowdStrike and Threat Intelligence, as well as various emails and the attachments from CyberCX and Coveware.

Medibank stated that the dominant purposes included:

- advising Medibank on its compliance with the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth)

- responding to compulsory OAIC notices

- identifying legal issues and risks (including those arising under Australia’s anti-money laundering, financing or terrorism and sanctions laws)

- briefing counsel and preparing Medibank’s defences in legal proceedings, and

- preparing advice to Medibank on steps it should take in relation to leaked data in order to comply with its legal obligations and mitigate any legal risk.

-

What was not privileged? Deloitte Reports

-

Medibank commissioned three reports including a ‘Post Incident Review,’ ‘Root Cause Analysis’ and ‘External Review – APRA Prudential Standard CPS 234’ (Deloitte Reports). The Deloitte Reports were found not to be protected by legal professional privilege for two main reasons:

- Multiple purposes: the dominant purpose of the reports was not to obtain legal advice or for the preparation of litigation but instead for other non-legal purposes.

- Waiver of privilege via public statements: Medibank’s voluntary disclosure through ASX Announcements and other public statements, which disclosed the 'gist or conclusions' and recommendations from the Deloitte Reports constituted a waiver of privilege.

Multiple purposes

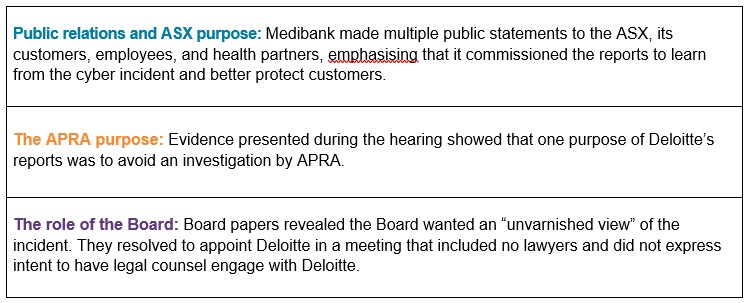

Justice Rofe found that the Deloitte Reports were produced for four other purposes in addition to the dominant purpose of obtaining legal advice or preparing for litigation. These included:

- operational

- governance

- APRA, and

- ASX and public relations purposes.

It was not disputed that Medibank commissioned the Deloitte Reports for legal purposes, but it was concluded that it was not the dominant purpose. Justice Rofe placed emphasis on the Board’s involvement with Deloitte where Deloitte directly reported its findings to the Board. the engagement with Deloitte was heavily influenced by APRA, which ‘informed the scope of the external review to ensure that it met APRA’s requirements.’ This aim was to avoid a separate review with APRA, which was identified as a dominant purpose of the Deloitte Reports.

Waiver of privilege through public communications

Justice Rofe concluded that even if the Deloitte Reports were protected by legal professional privilege, Medibank would have waived its claim by making public announcements.

Tips

It is essential that businesses consider various factors when conducting an investigation:

- During a cyber breach, many actions are taking place simultaneously.

- It is prudent to pause and reflect on the purpose of the various communications.

- Simply asserting a claim for legal professional privilege is not sufficient.

- Seek legal advice regarding the content of market communications and other public statements and be aware of the potential consequences.

- Assess whether the circumstances justify the preparation of different reports for different purposes.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the Court found that it 'did not consider that the provision of legal advice and/or assistance was the dominant purpose for which the Deloitte Reports were commissioned.'[6]

What is perhaps more important is that during a rapidly evolving cyber security breach—characterised by a whirlwind of information, misinformation, stakeholders, and questions—legal professional privilege can still be maintained.

To retain legal professional privilege, careful consideration must be given to the creation of the communications but also to the statements made about them (both before and after their creation), which can inform the reader about the author’s mindset regarding their creation.

[1] McClure v Medibank Private Limited [2025] FCA 167 at [218].

[2] Ibid at [176].

[3] Ibid at [180].

[4] Robertson v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1392 at [29].

[5] McClure v Medibank Private Limited [2025] FCA 167 at [186].

[6] Ibid at [323].