Building a fence around the digital playground

11 September 2025

An increase in online privacy risks for children has prompted the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) to develop a Children’s Online Privacy Code (Code). The OAIC’s mandate to do so was established under the Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2024 (Cth), and the Code has just finished undergoing a second round of consultation.

This article examines the development of the Code, including the concerns driving its creation, its intended scope, the challenges identified during the consultation phase, and how the United Kingdom’s regulatory approach is likely to influence it.

Digital risks to children

The push for a Code is a response to research findings that reveal increasing online digital risks for children. A vast amount of personal information is collected from children from an early age; estimates suggest that by the time a child reaches 13 years of age, 72 million data points may have been gathered about them.[1] This widespread data collection has prompted the Government to develop the Code, with the consultation paper stating that, ‘Existing privacy laws have not kept pace with these changes in digital engagement or the scale of data collection.’[2]

Origins of the Code

The timeframe for implementing the Code involves a three-stage consultation process, detailed as follows:[3]

- September 2023: Privacy Act Review Report released, including a proposal to introduce a Code.[4]

- September 2024: The Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2024 (Cth) was introduced.

- December 2024: the Bill was passed, becoming an Act.

- January 2025 (Phase 1): OAIC consults with children, parents and organisations focused on children's welfare.

- May 2025 (phase 2): OAIC engages civil society, academia, and industry stakeholders, to gather insights and perspectives on application of the Code and relationship with the APPs.

- June 2025: OAIC releases ‘Children’s Online Privacy Code’ issues paper[5], seeking stakeholder input.

- July 2025: Submissions close for the OAIC’s issues paper.

- Early 2026 (Phase 3): Proposed release of the draft Code and third and final public consultation.[6]

- December 2026: Proposed finalisation and roll-out of Code.

Scope and applicability across sectors

The Code is not intended to prevent children from engaging in the online digital world; rather its purpose is to protect their personal information in the digital space through enhanced privacy protections. Although the draft Code has not been released yet, based on the issues paper, it is expected to specify how certain services accessible by children must comply with the Australian Privacy Principles (APPs) under the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth).

The Code applies to businesses and organisations that provide ’Services likely to be accessed by Children’, ’Social Media Services’, ’Electronic Services’ and ’Designated Internet Services’ as defined in the Online Safety Act 2021 (Cth) (Online Safety Act). It also extends to any entity that is subject to the APPs or falls within a class of entities governed by these principles. However, it is important to note that the Code does not apply to entities providing health services, although it may apply to those offering health-related fitness or wellbeing apps and services.[7] This drafting aims to ensure flexibility by encompassing a wide range of entities while allowing the Code to specify which entities are exempt from its provisions.[8]

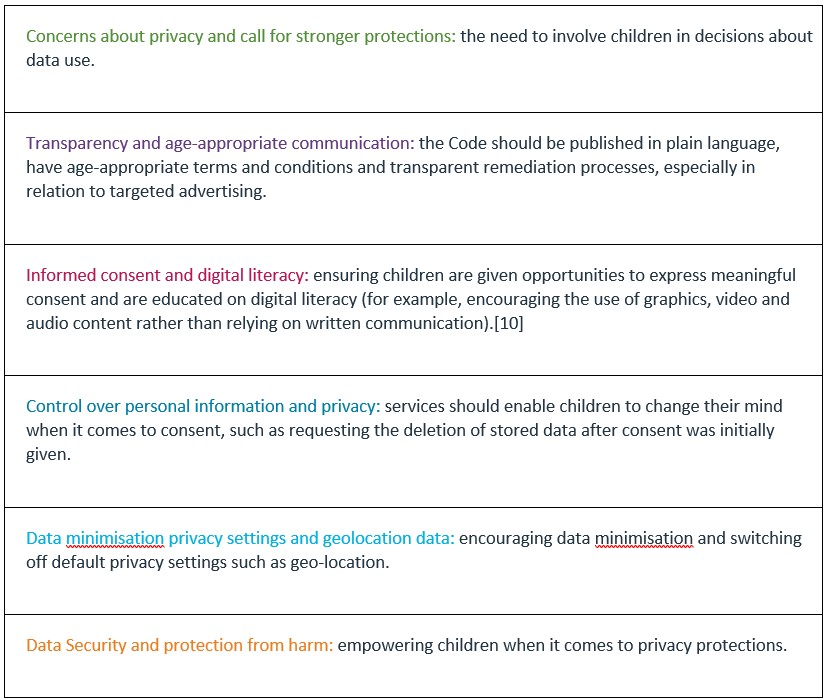

The OAIC’s issues paper provides insights arising from the OAIC’s previous consultation stage. These learnings, likely to inform the objectives of the Code, are summarised below:[9]

The Code will function as an enforceable APP code that outlines how protections in the APPs are to be applied or complied with in relation to the privacy of children.[11] The Code is likely to be based on the UK’s ’Age-Appropriate Design Code’ (the UK Code), which comprises 15 standards.[12] The most important of these standards codifies the ‘Best Interests Principle’.

The Best Interests Principle restricts the use of children’s data to situations where it is in their best interests. It requires this principle to be the primary consideration when designing and developing, apps, games, websites and other platforms likely to be accessed by children.[13] The other standards of the UK Code outline the types of conduct entities can engage in to ensure children are better protected online. These include ’turning off’ default settings that do not protect privacy and prohibiting practices by corporations that could harm the wellbeing of children. The Code may also introduce the ‘right to be forgotten’, allowing individuals to request deletion of their data upon turning 18.[14] Although this right already exists in the UK for all individuals, if implemented in Australia under the Code, it will only apply to children’s data.

Scrutiny from stakeholders

Phase two of the consultation process concluded on 31 July 2025. Stakeholders were asked questions about:

- The scope of services that should be covered by the Code

- When and how the Code should apply to APP entities

- Age-range specific guidance

- APP specific questions including transparent management of personal information, anonymity and pseudonymity, consent mechanisms, marketing restrictions, security requirements, international interoperability, and access and correction to personal information

Several organisations have made their submissions publicly available. These submissions reveal that while some industry participants support stronger privacy protections for children, they also want to ensure that compliance obligations are proportionate to the risks involved. Such a stance is evident from submissions that support protection for children online, but urge the OAIC to ensure that the compliance obligations will reflect actual risk and avoid interference with commercial operations such as insurance.[15] Other submitters contend that the Code applies too broadly, and proposes that OAIC explicitly exclude some APP entities from the scope of the Code at the outset so there is clarity around its application.[16] In addition, there have been recommendations around how the likely to be accessed by children (LTBA) test should be operationalised for online services.[17] Currently, the Act, specifies that it will be up to the Commissioner to make written guidelines to assist entities in determining if a service is likely to be accessed by children, which aligns with the UK’s LTBA test.[18]

Broader public initiatives shaping the national conversation on children’s online privacy

The development of the Code forms part of a broader government effort to address online harms. The OAIC will be consulting with the eSafety Commissioner and National Children’s Commissioner before registering the Code.[19] Consequently, broader public initiatives will be important to the Code’s formation. Some of these initiatives have included:

- The ongoing development and implementation of Online Safety Codes and standards [20]:

- The ‘Minimum Age for Social Media Access’ (the Ban), effective December 2025. While distinct from the Code, the Ban targets similar platforms such as those enabling user interaction and content sharing. The government has confirmed that platforms like Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and X will be included. Unlike the Code, the Ban is unlikely to apply to platforms focused on gaming, messaging, product or service information, professional networking, education, or health services.[21]

- A review of the Online Safety Act has been released. Key to the review was assessing whether there should be a ’digital duty of care’ for platforms to ensure user safety.[22]

- eSafety initiatives, such as Safer Together! and Leaving Deadly Digital Footprints! Have been developed specifically for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and their carers.

Conclusion

While the final form of the Code and the factors informing its development are beginning to take shape, offering insight into its potential operation and scope, some elements remain unclear. What we know for now is that the OAIC plans to release a draft Code in early 2026 for at least 60 days of public consultation, with the aim of having the Code in place by 10 December 2026.

If you missed out on the previous consultation period that closed on 31 July 2025, we recommend participating in this third and final consultation phase.[23]

[1] Office of the Australian Information Commissioner, Children’s Online Privacy Code Issues Paper (Issues Paper, 12 June 2025).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Association for Data-Driven Marketing and Advertising, The Privacy Series: The Children’s Online Privacy Code (Web Page, 2025).

[4] Attorney-General’s Department, Privacy Act Review Report (Report, 16 February 2023).

[5] n 27.

[6] s 26GC(9) of the Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2024 (Cth)

[7] Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) s 26GC(5)(7).

[8] Explanatory Memorandum, Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2024 (Cth), House of Representatives, 31 January 2025.

[9] n 27.

[10] n 34.

[11] n, 34.

[12] Information Commissioner’s Office (UK), Age Appropriate Design: A Code of Practice for Online Services – Best Interests of the Child (Web Page, 2025)

[13] Normann Witzleb et al, Privacy Risks and Harms for Children and Other Vulnerable Groups in the Online Environment (Research Report, Office of the Australian Information Commissioner, 18 December 2020)

[14] ABC Radio National, Could Aussie Kids Be Given the "Right to Be Forgotten" Online? (Life Matters, 17 August 2025)

[15] Insurance Council of Australia, Submission to the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner: Children’s Online Privacy Code (28 July 2025)

[16] Business Council of Australia, Submission in Response to the Children’s Online Privacy Code Issues Paper (July 2025)

[17] Reset.Tech Australia, Likely to Be Accessed: Children’s Data and the Case for a Privacy Code (2025)

[18] S 26GC(11) Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2024 (Cth)

[19] n, 34.

[20] Issued under Part 9, Division 7, of the Online Safety Act (2021) (Cth).

[21] Josh Taylor, How Australia’s Under-16s Social Media Ban Will Be Enforced – and Why TikTok, Instagram and Facebook May Be Exempt (The Guardian, 1 August 2025), Anthony Albanese Takes Kids’ Social Media Ban, Now Including YouTube, to the World Stage (The Nightly, 29 July 2025)

[22] Michelle Rowland, Report of the Online Safety Act Review Released (Media Release, Minister for Communications, 4 February 2025)

[23] eSafety Commissioner, Online Safety (Web Page, 2025)